We grew up with deaf parents — don’t call us ‘poor things’, say Singapore’s CODAs

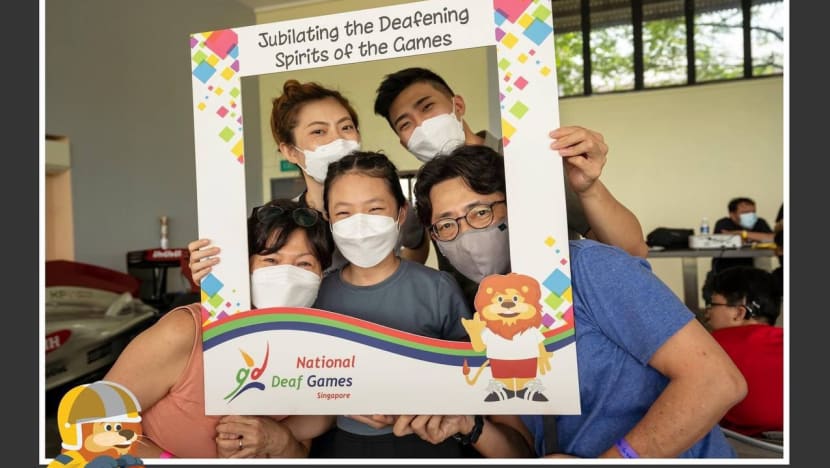

SINGAPORE: Christalle and Christophe Tay are often asked how they grew up. It might seem blunt, even insensitive, but the pair, 25 and 23 years old respectively, are used to it.

How did they learn to speak? How could they connect with their parents? How did they pick up sign language?

“It’s not malicious. These are very natural questions that people will think about,” said Christophe.

They are happy to answer, but it is frustrating for them when folks make assumptions. Other children of deaf adults (CODAs) whom CNA Insider spoke to feel the same.

One of Dhyaana Shona’s classmates who found out that her parents were deaf told her: “I’m so sorry you need to deal with sign language.”

That upset the 11-year-old. “Don’t be sorry! I’m not even sad that I know sign language. It’s a superpower for me,” said Shona.

Globally, it is suggested that nine in 10 children born to deaf adults are hearing. Most of them will pick up sign language and step up to help interpret conversations for their parents.

For these CODAs, deafness is integral to their identity, but at the same time it is only a small part of their life.

There are no estimates of the number of CODAs in Singapore, but this is what having a foot in both worlds is like for some of them.

LEARNING TO SPEAK AND SIGN

For as long as they were learning to speak, CODAs also learned to sign so that they could connect with their parents.

Grace Phua’s earliest memory is of her mother drawing an animal on a whiteboard with its name, pronouncing the name as best she could and demonstrating the sign for it. She would then correct her children’s hands as they copied her.

“(My parents) taught me a lot about expressing yourself. When they tell stories, it’s really colourful and vibrant,” said the 31-year-old.

Christalle and Christophe could hardly pinpoint when they picked up sign language. “It’s exactly like how you learnt to speak English … through association,” said Christophe, an undergraduate.

For example, you may have learnt to say “milk” when your parents gave you a bottle and said the word, he cited. “As you associate these actions with the things you’re seeing, you start to learn.”

By seeing their parents raise a hand, faced inwards, and open and close it a few times — paired with their milk bottle — they learnt that doing the same would give them milk.

The next thing they knew, they were signing their bedtime stories and the Bible along with their parents. “I say it’s my first language because it’s the first language I felt,” said Christophe.

In fact, their parents said they learnt to sign before they spoke, added Christalle, a National University of Singapore analyst.

Learning to speak is a different challenge, since home can be a “silent world”, as Shona’s mother, Shalini Gidwani, said.

The sign language teacher lost her hearing at the age of four after a high fever, while her husband Gohpi Nathan was born deaf. While they can both voice words as they sign, their pronunciation is “not as clear” as it is for hearing people.

With hearing loss, deaf people are unable to hear exactly what normal speech sounds like, leading to a lack of natural inflections when they speak, according to an article in Verywell Health. This is known as “deaf speech”.

So if CODAs do not have the opportunity to listen to and interact with carers who communicate orally, they may experience delays in developing speech, said Shobhana Wamb, a senior speech and language therapist from Canossaville Children and Community Services.

WATCH: I’m 10, she’s 11. We’re CODA (children of deaf adults) in Singapore (10:11)

But it does not mean they will not develop speech, as there are many ways parents and educators can provide rich language and listening exposure for these children, she added.

Typically, at around six months to before a year old, infants should engage in vocal play and babbling and acquire skills such as making sounds in reply to someone talking to them

That was when grandparents were a big help to Shona and her 10-year-old sister, Dipikha Soniya, who grew up with them close by.

Television shows such as Hi-5, Veggie Tales and Disney classics were also played at home. This was how the girls developed their love of singing and dancing, even if their parents could not fully understand.

In the case of the Tay siblings, there was even a time when they spoke better Mandarin than English, thanks to their grandparents.

As for Grace, her parents bought a piano and a drum set and encouraged her and her three siblings to play music. “It’s quite funny. I thought my parents were familiar with songs like Mary Had A Little Lamb,” she said.

“I realised they didn’t only when I was much older. Because when I was playing the piano, they always pretended they could hear and clapped along.”

Speaking to adults, however, proved a challenge for Grace, who now runs a marketing agency. Without talking much to her parents and other relatives at home, she grew up quiet and reserved.

“I didn’t dare to speak up. I wasn’t comfortable using my voice,” she said. “Even now it feels a bit weird when I see my friends talking to their parents. And sometimes I’d be overly polite when I talk to other parents.”

STEPPING UP AS INTERPRETERS

Being CODAs also means having to step up in the family, even from a young age.

Once they could sign properly, which was around seven years old, said Christophe, they began to interpret for their parents, such as when the bank or telecom providers called.

As the eldest child, Christalle felt like she had to “grow up a bit faster”. “You need to understand more technical terms to interpret for them,” she said.

And you normally don’t hear things like, ‘Your mum has this much in her bank account.’ Being put in those situations … I just worry about those things a lot more.”

Being shy growing up did not make it easy for the two siblings, who have a younger sister, 13.

“We hated speaking to peers, much less adults. (But) we had to tell waiters, ‘The food’s not nice’ or ‘Can we change this?’” said Christalle. “Simple things, but it was very scary for us.”

Shona and Dipikha, meanwhile — described by their mother as “confident” and “talkative” — take pride in using their “superpower” every chance they get.

Shona recalled an incident when they were emceeing a school concert their parents attended. As they spoke into the microphone in one hand, they did “little finger signs” with their other hand, even though their teacher said not to fidget.

“When (my parents) don’t have an interpreter, they don’t understand what’s going on,” said Shona. “I don’t really care if a teacher will scold me.”

The girls have been their parents’ little helpers for as long as they can remember: Alerting them to someone at the door, responding to missed calls and helping to order food at the hawker centre.

They have even got used to dealing with “mean” people, said Dipikha. “We’re just dealing with what we’ll deal with in future. So we’ve got some experience.”

Shona, for instance, told off an impatient food vendor not too long ago. While waiting for the girl’s mother to order, the vendor said: “Hurry, hurry, hurry. If you don’t want (to), just go to the back lah!”

When Shona pulled her mask down so her mum could lip-read, the vendor threatened to call the manager, even though she explained that her mum was deaf.

“Then I’m like, ‘Call the manager lah!’ What did I have to lose?” she recounted. In the end, the manager and vendor apologised.

Sometimes they might overstep their role as interpreters, the Tay siblings shared. In some instances, it felt “natural” to settle things on their parents’ behalf, they said.

When they take a call, for example, it can be difficult to juggle between listening on the phone, signing to their parents and then communicating their parents’ opinion, cited Christophe, who sometimes has asked them to wait for him to explain the situation to them later.

“It makes them feel like they’re being excluded from the conversation,” he acknowledged. “The thing is, what we need to do is to interpret for them and give priority to their voice rather than be rushed by the telephone operator.”

They now make a conscious effort to do so.

TOGETHER, FOREVER?

The lives of CODAs have been in the spotlight recently since the film CODA bagged Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards.

The film revolves around a daughter — the only hearing person in her family of four — torn between pursuing her passion for music and her parents hoping for her to stay and help with the family business. They relied on her as an interpreter for business dealings.

Is there a similar tension for Singaporean CODAs?

Christalle and Christophe have no qualms about moving out in future. They do not see their parents as reliant on them, though the siblings are protective towards them.

Their father is a private-hire car driver and a part-time sign language teacher at Equal Dreams, which provides consultancy and services to promote disability inclusion and accessibility. Their mother teaches sign language part-time to pre-school children in a Singapore Association for the Deaf programme.

“It’d only be (a worry) if people come and confront them … because they don’t know (my parents) are deaf. But I think (my parents) can handle it themselves,” said Christalle.

With doorbells fitted with lights to notify them and cameras at the door, the siblings are not too worried about their parents living alone.

Their parents have also managed visits to the doctor’s mostly on their own, Christalle added. “If we go, it’s in our capacity as a child out of concern.”

Grace, on the other hand, is “slightly reluctant” to move out as she sees her parents getting on. Her dad, a retired pastor, is 68, and her mum, a housewife, is 63.

“I feel like it does help that I’m around. It makes things easier if they’ve got someone to answer the doorbell,” she said.

While Shona and Dipikha feel that their parents need them, the adults do not expect that of them. “I can’t possibly rely on my daughters all the time. They should have their own space. We know English, no problem,” said Gohpi.

He also prefers to handle matters such as appointments at the doctor’s or the bank on his own. “There are many types of hard words that the children don’t understand. I understand. I can write, I can text. I want to communicate directly,” he said.

But what is frustrating, shared the CODAs, is the lack of accessibility and sensitivity faced by the deaf.

For example, this happens when banks are not accommodating and insist on settling things over the phone, said Christalle. One bank even insisted that their parents submit “something like a power of attorney” to authorise their children to speak for them, she cited.

It happened when primary school classmates asked Grace, “When I say they’re stupid, (your parents) can’t hear?” And when folks assumed that she and her siblings were such “poor things”.

It also happens during family outings, when people give them weird looks as they talk to each other, said Shona.

A SENSE OF PRIDE

Although growing up with deaf parents has its difficulties — like when she struggled to get their attention or when they had no idea the vacuum cleaner blaring away in the living room was disrupting her work, Grace cited — they are like any other parents.

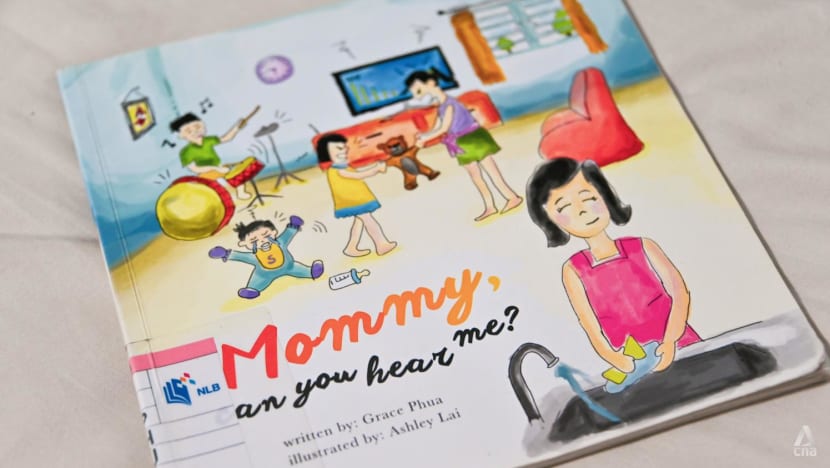

And she wants more people to know about it through a children’s book she wrote and dedicated to her mother: Mummy, Can You Hear Me?

“I wanted to celebrate my mum, to show that she’s like any other mum. She can do a lot of things like cook, and she was a good maths teacher,” said Grace. “My parents are very strong.”

Indeed, if you do ask Christalle and Christophe how they grew up, they will say it was fun and their family was affectionate.

“We talk a lot. Sometimes we end up being in someone’s room, and we’ll just be talking about our day,” said Christalle.

“We sign ‘I love you’, and we hug each other … something I’ve just started to realise is hard to find in other families,” said Christophe. “It’s very hard for us to say our life sucks”.

Above all, they take pride in their “semi d/Deaf identity”. The capitalised ‘D’ describes people who identify as culturally deaf and use sign language to communicate.

“I feel very connected to this identity; I can’t separate it,” said Christophe.

No comments

Share your thoughts! Tell us your name and class for a gift (: