‘In 10 years, we may no longer be here’: Johor’s Orang Seletar threatened by dwindling seafood catch

An Orang Seletar fisherman at work along the Johor Strait, off Kampung Sungai Temon in Johor Bahru. (Photo:CNA/Amir Yusof)

JOHOR BAHRU: Mr Kun, a prawn fisherman of the Orang Seletar community in Kampung Sungai Temon, was getting exasperated.

He had been motoring his boat between various spots across the fishing bay since 6am on Saturday (Jun 18) morning, reeling in empty pink nets from the steel-coloured water.

But as the hours passed until it was almost 10am, he could not net a single prawn.

“This is getting more common these days, going home empty-handed,” said Mr Kun, who goes by a single name.

“I needed to catch 1kg (of prawns) to cover my boat fuel costs so today, I’m wasting my energy, at a (financial) loss,” he added, wiping off beads of sweat from his brow.

Mr Kun is one of the fishermen of the indigenous Orang Seletar community, who has for centuries lived at the Johor Strait that separates Malaysia and Singapore.

Like many others in his community, Kun said that his catch and earnings have diminished rapidly in recent years.

“Back in 2005 to 2010, I was catching 5kg to 6kg (of prawns) on most days. Those days are long gone now,” he added.

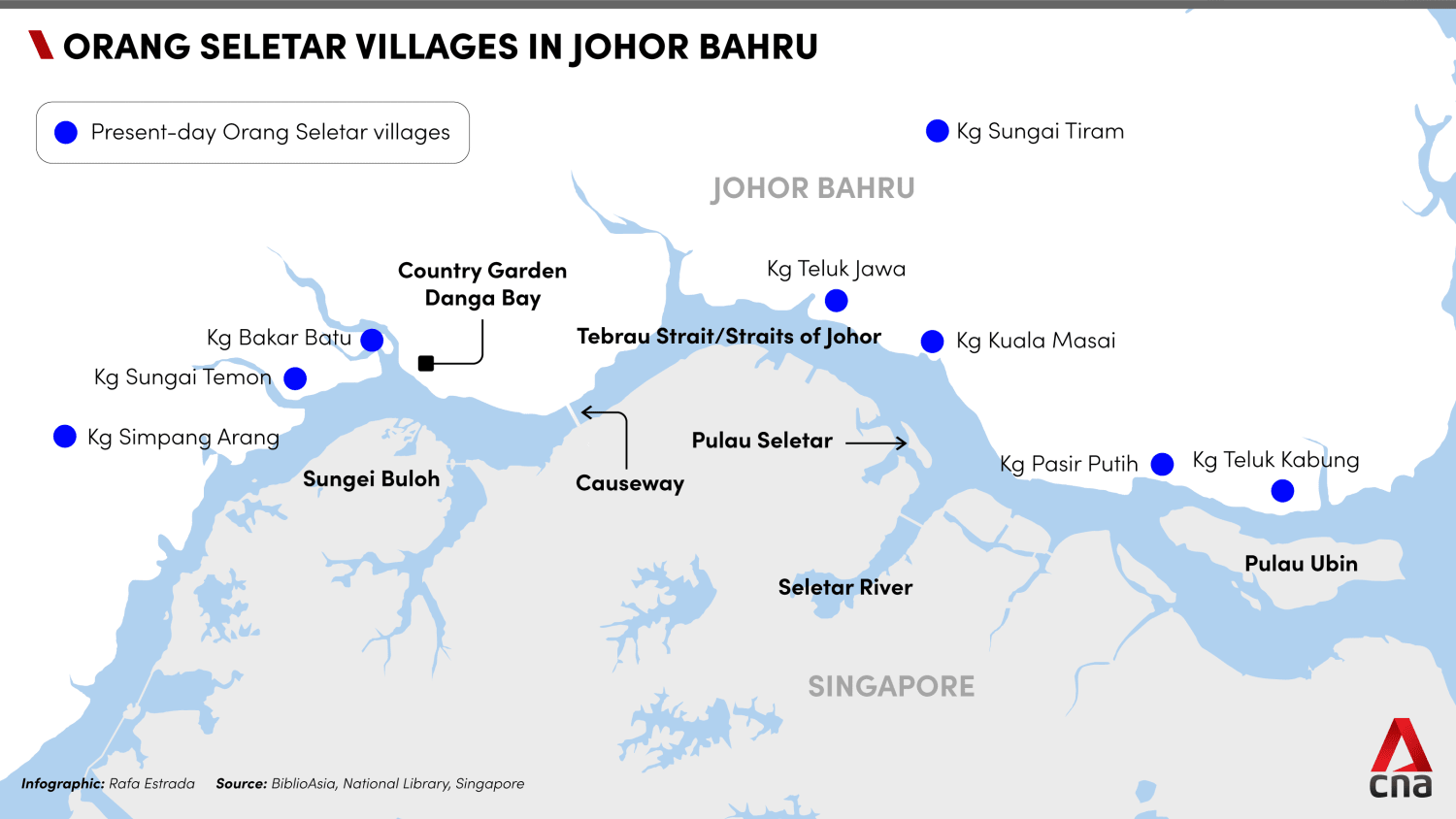

The Orang Seletar were once nomadic sea people, who lived along the rivers and shores in the northern part of Singapore and the southern side of Johor.

Since 1965, most of the Orang Seletar have settled in eight villages in Johor Bahru, while those in Singapore have assimilated with the larger community.

These Orang Seletar communities in Johor Bahru have a combined population of around 2,000. Some of them have expressed concern that their main source of livelihood - seafood catch on the Strait of Johor - has been dwindling dramatically in recent years.

Observers CNA spoke to have attributed this to environmental factors such as climate change as well as the impact of land reclamation projects along the Johor Strait.

EXTREME WEATHER PATTERNS MAKES IT HARD TO FISH

Malaysia’s report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2019 indicated that its temperature has been rising for the past four decades, a trend that is projected to continue for the next 30 years.

Average temperature in Malaysia is projected to increase by between 1.2 degrees Celsius and 1.6 degrees Celsius by 2050, the report stated, leading to various implications such as extreme weather and unpredictable waters off its coasts.

Dr Serina Rahman, a visiting fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute who is also a conservation scientist, told CNA that global warming is supercharging the weather at the Johor Strait towards greater extremes, and fishing communities such as the Orang Seletar are at risk.

She recently published an academic paper on how climate change has contributed to a stark drop in fish landings for fishermen in southwest Johor.

“It's much harder to get the same amount of catch - they have to take longer at sea, go further and they get less in spite of the additional effort,” she said.

“Warming sea surface temperatures increase the frequency of extreme weather. Stronger storms and winds. Erratic wind changes. Things don't follow the patterns of years past and happen out of season,” she explained.

“Very simply, crazy weather means they can't go out to sea in their small boats. This means less money for them.”

Mr Adam, an Orang Seletar who fishes for flower crabs off Kampung Bakar Batu for a living, told CNA that his overall catch and resultant earnings have dipped by 70 per cent as compared to 2012, a decade ago.

He attributed this partly to what he regarded as “crazy weather” and acknowledged that his small wooden boat makes it hard to go out during storms.

“Just look at what has happened this year for instance - regardless whether it's January or March or June, the storms have been bad and many days I cannot risk going out,” said Mr Adam, who goes by one name, in the native Kon Seletar language. He was speaking to CNA through a translator.

“I was caught in a heavy downpour once. My boat was filled with water and I had to pay to get it repaired,” he added.

Mr Kun, the prawn fisherman, echoed similar sentiments.

“The heavy rain and strong winds are getting more frequent. It's harder for me to pull up the nets during storms,” he added.

He too said his overall earnings from fishing had dropped “more than half” over the last decade, partly because of the weather.

LAND RECLAMATION ALSO DIMINISHES FISHING CATCH

Dr Serina noted that development projects along the Johor Strait, which involve land reclamation, have also diminished seafood catch for the Orang Seletar.

“As shorelines expand, seas become smaller. Fishermen struggle to get to sea as marine areas are carved out for private or industrial use,” she said.

“The whole stretch of the Johor Strait faces development pressures and the impact on marine habitats in the area affects everyone - local fishermen and all the orang asli who fish along the strait as well,” she added.

She noted how, for instance, that land along the Danga Bay is being used for a myriad of development projects, including residential and commercial purposes. She added that this impacts the Orang Seletar directly, especially those who reside at Kampung Sungai Temon and Kampung Bakar Batu.

A fisherwoman, who wanted to be known only as Mina, was catching mussels near Kampung Sungai Temon when she told CNA that a large dune of sand currently looms over her village, spilling into the shoreline.

She claimed that it was placed there by a land developer “some years ago”, as part of the initial process of reclamation.

“This place used to have mangroves, and there used to be abundance of crabs, prawns as they lay eggs on the banks,” said Mdm Mina.

“But now there’s this big mountain of sand, and we have to dig deep to find anything. It’s difficult work, but such is the plight of the Orang Seletar,” she said while on her knees, raking the sand surface with a hoe.

She had been digging the base of the sand dune for three hours, and only managed to collect less than two dozen mussels. She said that back in the 90s and early 2000s, for the same amount of time spent, her basket would be full with mussels and other seafood catch.

The sand dune, along with other land reclamation projects in the Danga Bay area, have been the subject of an ongoing legal case involving Orang Seletar and the state government.

In 2011, 158 Orang Seletar people started a class action suit against the Johor state government and 12 other parties to cease encroachment into what they perceived to be their native customary land.

In 2017, the Johor Bahru High Court ruled for the Orang Seletar, ordering the Johor state government to compensate for the loss of their customary land, based on market value.

Yet, until today, the case has yet to be resolved, according to Mr K Mohan, the solicitor representing the Orang Seletar for the suit.

Mr Mohan told CNA that all parties involved in the case were appealing the decision by the High Court, and the Orang Seletar were still determined to win back their land instead of receiving the compensation awarded.

“We all want an amicable solution to this problem, a happy ending for all sides. For us, what is important is that the Seletar communities are able to continue living in their land and fish in the waters with no disruption to their livelihood,” he added.

The Johor state government declined to comment when approached by CNA.

ORANG SELETAR’S WAY OF LIFE COULD BE THREATENED?

The impact of climate change as well as land reclamation projects on the Johor Strait are threatening the continued existence of the Orang Seletar, said Mr Jefree Salim, a mussel fisherman who lives in Kampung Sungai Temon.

“If it's difficult for us to continue earning a living, the Orang Seletar will move out or even find other sources of work in town,” said Mr Jefree, whose father Salim Palun is the tok batin or village head of the Orang Seletar community in Kampung Sungai Temon.

“In 10 years, we may no longer be here. The Orang Seletar may be forced to move away from our land and water to make way for more projects and coastal developments,” added Mr Jefree, who farms mussels on a floating platform on the Johor Strait and sells them to seafood restaurants in the city.

However, he acknowledged that the area his community lives on is prime land for residential and commercial development, due to the proximity to Johor Bahru and Singapore.

“I’ve been told by village elders that we may have to start considering alternative places to live, perhaps a settlement in Ulu Tiram (further up north of Johor),” said Mr Jefree.

“It’s sad because for centuries, we have been based here in the Johor Strait. It has been our home for so very long,” he added.

Mr Mohan, the lawyer, stressed that whatever happens in the long term, it is important that the Orang Seletar be allowed to continue their way of life.

“The important thing is wherever they are settled, they are allowed to live in peace and fish in waters with enough catch for their livelihoods. If not, the Orang Seletar community could soon be wiped out,” he said.

Dr Serina maintained that the communities like the Orang Seletar are at risk of losing their homes as indigenous land rights are not always recognised.

“This can happen to any coastal community with less power, clout or money because development is business, which is money important for a state that must build its economy,” said Dr Serina.

“Ideally, in a perfect world, we should work on finding a balance among money, development and a rich cultural history of a people who are highly endangered. But that of course will be hard to achieve,” she added.

CNA has reached out to the Johor division of the Orang Asli Development Department (JAKOA) for comments on the assistance provided to the community.

No comments

Share your thoughts! Tell us your name and class for a gift (: