Singapore’s prison without walls made the world sit up in 1960s. How did it fall apart?

The Pulau Senang settlement grew out of an idea to build a ‘moderate prison’. The experiment won praise, but reports of brutality later surfaced. It ended in a deadly riot in July 1963.

Many officials including the then Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew (third from left), visited the Pulau Senang penal colony. (Photo: Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore)

SINGAPORE: It was a prison-without-walls experiment on a Singaporean island that won global attention and inspired hope that secret society members could be rehabilitated through work.

In three short years, that hope turned to ashes, with the island settlement burned to the ground and its superintendent hacked to death.

What went wrong?

The two-part documentary Riot Island pieces together the intriguing rise and demise of Singapore’s first and only open-air prison on Pulau Senang — and the lives forever changed by it.

THE GENESIS

The Pulau Senang settlement grew out of an idea to create a different kind of prison at a time when those on mainland Singapore were overflowing.

Secret societies had spiralled out of control in Singapore by the 1950s, and gangs were terrorising the public and running gambling, prostitution and drug-related activities.

This contributed to prisons being overcrowded, said historian Donna Brunero of the National University of Singapore (NUS), “because you’re detaining many suspected criminals, but you’re unable to bring them through the entire legal process”.

C V Devan Nair, one of the leaders of the anti-colonial movement at the time, was a proponent of the Pulau Senang experiment. Having spent two stints as a political prisoner in the 1950s, he “developed an interest in prison rehabilitation”, said his son Janadas Devan.

After his second release in June 1959, Devan Nair persuaded the then government to set up a commission on prisons, said Janadas. One of the ideas for prison reform was the creation of a “moderate prison”.

Pulau Senang, one of Singapore’s southernmost islands — lying 13 kilometres from the mainland — was the site chosen.

Its name means “island of ease” in Malay. And it was “safe to use” as a penal colony as it was supposedly surrounded by shark-infested waters and strong currents, making escape difficult, said Kevin Tan of the NUS’ law faculty.

‘NATURAL LEADER’ PICKED TO RUN IT

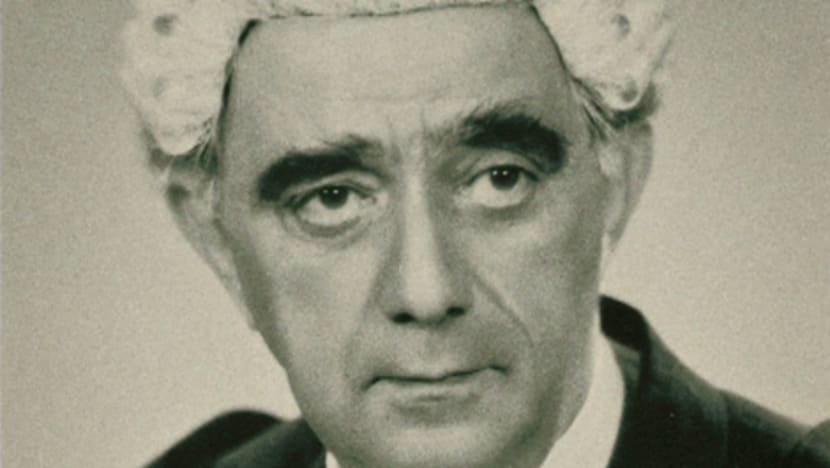

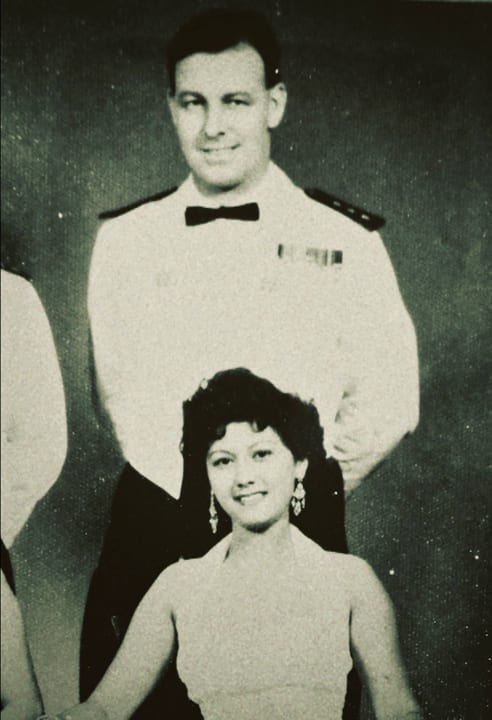

The man picked to run the open-air prison was a Briton: Daniel Stanley Dutton. He was well-regarded, could speak local languages including Malay and Hokkien and had worked in the prison services, said Brunero.

“He was married to a Malay woman, so he was someone who had community connections. He was someone who really had a vested interest in seeing Pulau Senang succeed,” she added.

Dutton was spoken of as someone who could “build anything with his hands”, said Tan. “He was a ground-up type of person. His superior described him as a natural leader of men.”

As superintendent, he was given a free hand to pick which detainees to take to the jungle-covered island. He arrived in May 1960 with 51 of them.

Within the first year, the number of detainees grew to about 120, and they built a “substantial amount of the infrastructure” on the island, said Brunero, who specialises in the history of the British empire in Asia.

Dutton gained the respect of the men by working as hard as them. In the early days, before the dormitories were built, he was “sleeping in close proximity to the detainees” — a sign of the rapport that had developed, added Brunero.

And despite not having “that many” guards on the island, they did not carry firearms, pointed out Hamzah Muzaini of the NUS’ department of Southeast Asian studies.

According to news reports, the facilities built included a hospital, recreation grounds and offices. The detainees also engaged in farming.

The progress of construction was “so amazing” that the United Nations took notice, and a film was also made, said Tan. Criminologists and policymakers round the world sat up.

“They thought, ‘Wow, if Dutton can achieve … so much with this group who were classified as hardened criminals, imagine what else could be done',” said Tan.

Brunero added: “The UN was particularly excited about this project because there’d been open prison experiments in the United Kingdom, in the United States and in Europe, but this was specifically a project to rehabilitate secret society members.”

Dutton, meanwhile, was named a Member of the Order of the British Empire, remembers his half-brother, Michael.

Politicians including the then Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, and the then Home Affairs Minister, Ong Pang Boon, visited Pulau Senang. So did Devan Nair, who even took Janadas along — and the latter recalled receiving his first swimming lesson from one of the detainees.

In an article in The Straits Times in September 1962, Devan Nair wrote about the “living proof of the value of free and creative labour in pleasant surroundings as the means of rehabilitation of hardened offenders”.

In 28 months, about 200 men had been returned to society after the “social therapy of Pulau Senang”. Their recidivism rate was 5 per cent, “surely about the lowest … in the world”, he wrote.

“Can you count that as a success or not? I’d say yes,” said Tan.BUILD, BUILD, BUILD, OR ELSE

But cracks began to appear in the rosy picture and in Dutton’s conduct. There were reports of the detainees being made to work relentlessly. They were reportedly asked to work at night “because it suited the timetable better”, cited Brunero.

“The dormitories had been built, the canteen had been built, roads had been laid. Why was Dutton still pushing long working hours and being really demanding?”

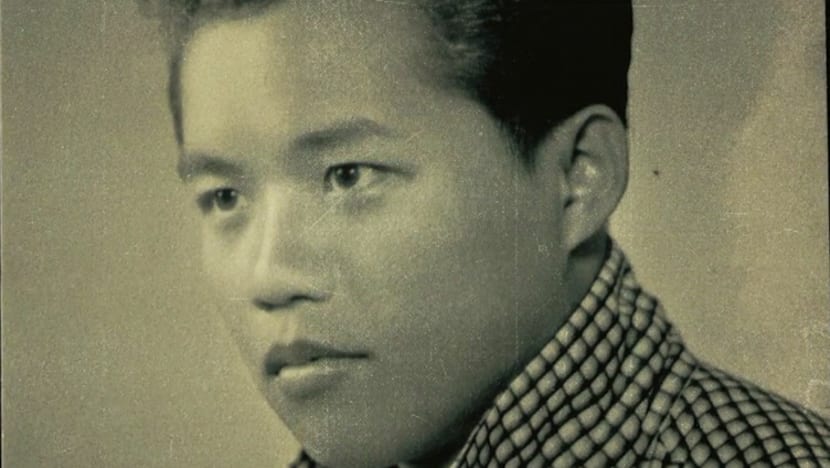

Neivelle Tan, a gangster turned pastor, spent a brief time on Pulau Senang but heard other detainees’ accounts darken over time.

Some of them were once “quite excited” about going to Pulau Senang and reported that it was “very nice” on their trips to the mainland for medical treatment, he recounted in oral history interviews with the National Archives of Singapore.

“Then the reports of the brutality came in,” he said. “Dutton would wake them up and march them into the sea when the tide was low enough to pick up the big boulders … and carry (them) to a certain place where there was a project going on.

“It could be a fish pond … a garden (or) just some decorative walls he was going to build.

“He’d be there supervising the work, shouting away, cursing. … I guess he was the typical example of a slave driver. You either do (the work) or you get punished.”

Those who misbehaved could be sent back to Changi Prison and its harsher living conditions.

Former prison officer Jimmy Chew confirmed some of the detainees’ dissatisfaction. “A few of them had been very badly treated or beaten up by (Dutton),” he said in an oral history interview, describing the superintendent as “very burly” and “very strict” with the detainees.

Dutton was the kingpin but was not the only one the prisoners disliked. There was “Ah Chia”, recalled former detainee Tan Sar Bee, referring to rehabilitation officer Chia Teck Whee.

“He appeared kind, but he always wrongly charged people. It was he who locked people in solitary confinement. People said he had a heart of evil. He was a bully.”

The former detainee had served in the Singapore Infantry Regiment and was training with the police reserve force when he injured someone and was accused of being a gang member, which led to his detention. He died this month.

He was on Pulau Senang in 1963 for less than three months. But besides what he saw, “there were always rumours” of corruption too, said Brunero.

Prisoners on the island hoped to be released if they behaved well, but when some of them saw others released after shorter periods, it led to questions as to what was going on, cited NUS political scientist Bilveer Singh.

THE WARNING SIGNS

One person who spoke out against the Pulau Senang experiment was former Chief Minister David Marshall, though he “didn’t challenge everything”, said Singh. “He thought re-education was good. However, he still believed that (the detainees) were being treated very badly.”

Marshall went to the island in 1963 and was “unhappy with what he saw”, said Tan the law professor. “He thought that there was an aura of fear pervading the island … (and) thought the conditions bordered on slavery.”

The weather was “extremely hot” on the day he visited, but many detainees were doing “extremely arduous physical labour”, said Brunero.

As a member of the Singapore Legislative Assembly at the time, Marshall tried to raise his concerns there, “but it seemed that no one paid attention”, Brunero added.

Those events were a deadly riot and fire.

There were two smaller instances of unrest leading up to the final act. One occurred three months earlier, when 14 detainees working in hot weather attacked an attendant after they had been refused water. They then fled into the jungle, and a reserve unit had to be called in to restore calm, said Brunero.

The second occurred about a week before the riot. Dutton was inspecting a jetty and found it to be unfinished. He demanded that the 13 carpenter detainees complete the work, but they refused, according to Chia.

It was Saturday, a rest day. But after they refused, Dutton told a clerk to prepare charge sheets and send them back to Changi. The men were marched down to the jetty and put in a prison boat.

This turned out to be the last straw.

“The biggest fear — (for) anyone who went to Pulau Senang — was (of) being sent back to Changi,” said Tan, who is also a former president of the Singapore Heritage Society.

“First, you lose the number of months that you spent on the island. And secondly, Changi wasn’t a very attractive place to be.”

After that, detainees from the different gangs banded together and talked about killing Dutton. One of the detainees, Chong Sek Ling, was an informer, and he warned Dutton.

But in his overconfidence, Dutton laughed it off, in the same way he disregarded earlier directives from the director of Singapore Prisons, Major Peter L James, who wanted the detainees’ working hours to be scaled back.

James also tried warning Dutton that he had been too harsh in sending the carpenters back to Changi.

“(Dutton) was absolutely confident that the majority of the detainees were with him,” said Tan. “You could say that this was probably Dutton’s delusion.”

THE FIERY, TRAGIC END

The rioters struck after lunch on Jul 12, 1963.

They picked up their machetes and hoes and went after their respective targets. “The rioters were shouting and running amok,” said Tan Sar Bee, who witnessed this from the island’s hospital. “They fought from the dining room to the office.”

Dutton ran into his office and shut the door. The rioters decided that if he did not come out, they would set the building on fire. Two of them chopped a hole in the roof, poured petrol through it and lit a match.

The place went up in flames, and Dutton ran out. Men with machetes and axes were waiting, and he was butchered with a “shocking” level of ferocity, said Brunero. His body was mutilated and burnt.

Three other prison officials were killed as the penal settlement came to a fiery end. Pulau Senang, along with other nearby islands, is now part of the Southern Islands Live Firing Range, where military exercises are conducted.

In November 1963, 59 detainees went on trial for rioting and murder. A special dock had to be built for the accused, and they wore numbers so the jurors could remember who was being examined, said NUS’ Tan.

After 64 days — the longest, biggest trial Singapore had hitherto seen — 18 men were found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang; 29 were jailed for rioting or rioting with deadly weapons; and the rest were acquitted.

It was a “terribly tragic chapter — that something with so much hope … could become so violent and so deadly”, said Brunero.

Dutton’s wife, Vickie, was “crushed” when the “love of her life” died, said their granddaughter Ferlynna Muhalib. The couple were constantly together at society events, and Vickie — a designer, model and writer — was a “darling of the press”, said art and fashion historian Nadya Wang of the Lasalle College of the Arts.

On the sentence passed on the 18 men, Ferlynna said: “For what they did to Danny, they deserved to die.”

Michael Dutton, who recently visited his half-brother’s grave for the first time, had this message for him: “You proved that redemption was possible through hard work. But you were dealing with some very hard-nosed people.

“You still came out, to me, as the winner because you proved that the system would work.”

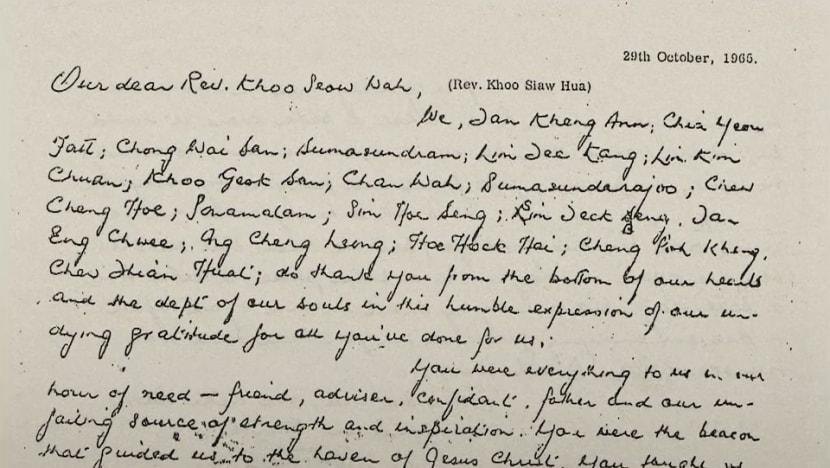

The 18 condemned men were provided with pastoral care by prison chaplain Khoo Siaw Hua, who went to their cells every day until the execution, said his grandson Timothy Khoo. “So his journey with them was very, very personal, almost intimate in some respects.”

One of the men, English-educated Tan Kheng Ann, penned a farewell letter to the chaplain that was signed by everyone. He wrote of the group’s “undying gratitude for all you’ve done for us”.

“It is with a heavy heart that we must now bid thee goodbye, but we know that we will see you again one day — in a better place, a better time, a better day,” concluded the letter.

Assuaging their anxiety in the face of death, the 18 sang as they made their way to the gallows on Oct 29, 1965.

No comments

Share your thoughts! Tell us your name and class for a gift (: